Portugal’s best corn dishes (and where to eat them in Lisbon)

Corn isn’t native to Portugal, but it has been part of the national diet for so long that it feels like a solid element of our culinary identity.

When Portuguese sailors encountered maize in the Americas in the early 1500s, they quickly recognized its potential. Unlike spices or cacao, destined for the wealthy, maize was practical, as it was high-yield, filling, and able to feed humans as well as livestock. By the second half of the 16th century, it was already cultivated in the northern regions of Minho and Douro, where locals called it big millet (milho grosso), to distinguish it from the smaller millet they had grown for centuries.

The northern climate was ideal for the corn crop. Where wheat often failed, maize thrived, giving more grain per hectare and providing fodder for animals. Soon, its cultivation spread south into the Beiras, across to Trás-os-Montes, and into the Algarve, where white maize became the base for xerém, quite similar to the Italian polenta. From there it reached the islands of Madeira and the Azores, where it was quickly introduced into local diets.

Feat photo by TeleCulinária

Photo by Fototeca Municipal de Lagos

Photo by Fototeca Municipal de Lagos

For centuries, wheat bread remained a marker of wealth, while broa de milho, dense, dark, and sustaining, was the bread of the working classes, who would gather to cook their bread at communal wood-fired ovens.

But the relationship between Portugal and corn was never entirely smooth. By the 18th century, pellagra, a disease caused by niacin deficiency, was being reported in rural areas where diets depended almost exclusively on maize. The problem lay in the way corn was prepared. In Central America, where maize had been a staple for millennia, people used a technique called nixtamalization (which is still very much in use), which consists in soaking and cooking corn in an alkaline solution, usually limewater, which unlocks the niacin in the grain and makes it bioavailable. In Portugal, however, this method was unknown, and corn was simply ground and cooked as flour or meal. Without nixtamalization, the grain lost much of its nutritional value, and when eaten in isolation it could lead to malnutrition. Doctors warned against overconsumption, but for poor communities maize was cheap and satiating. For generations of farmers and fishermen, a slice of broa with soup or cheese meant a belly relatively full and survival for yet another day.

Photo by Restos de Colecção

Photo by Restos de Colecção

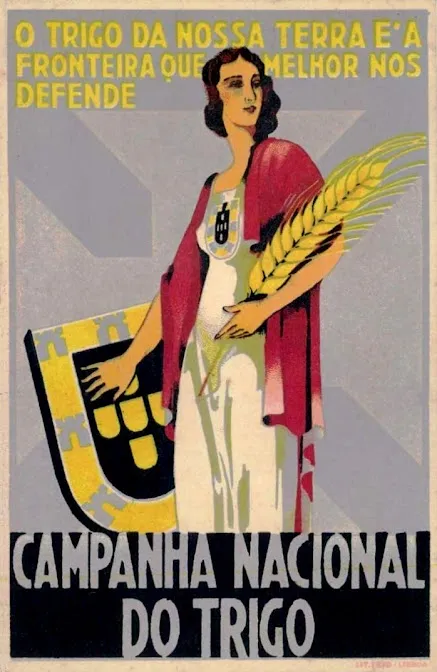

The 20th century brought another turning point. Under Salazar’s Estado Novo dictatorship (1933-1974), agricultural policy shifted heavily toward wheat. Wheat was politically useful as it symbolized modernity, progress, and self-sufficiency, and the regime launched campaigns such as the Campanha do Trigo (Wheat Campaign) to promote its cultivation, particularly in the Alentejo. Corn, associated with poverty and the North, was pushed aside. Broa was stigmatized as “the bread of the poor”, while white wheat bread was held up as the ideal national staple. This official preference altered consumption patterns, especially in urban areas, and marginalized corn related traditions that had been central for centuries.

Even so, maize never disappeared. In rural communities, people kept baking broa, preparing porridges, and frying milho frito, and so these traditions persisted in family kitchens and local festivals. After the Revolution of 1974, Portugal gradually re-embraced regional diversity, and corn regained cultural value as part of the country’s gastronomic heritage.

Today, though Portugal produces less maize compared to some European neighbors and relies heavily on imports, dishes made with milho remain iconic. Folklore even preserves its significance with proverbs like “Quem semeia milho, colhe pão” (“Whoever sows corn, reaps bread”).

While in Portugal, we recommend you to try some of the most iconic Portuguese corn dishes we list for you hereunder.

Corn breads from across Portugal

Broa de milho | Portuguese corn bread

Photo by Gleba on VendusGO!

Photo by Gleba on VendusGO!

Broa de milho is perhaps the most emblematic corn product in Portugal. This is the rustic bread of the North, baked for centuries in Minho, Douro and Beiras, where corn cultivation thrived after the grain’s arrival from the Americas. Unlike wheat bread, which was historically associated with wealth, or rye bread, which carried a reputation of being harsher and heavier, broa became the daily bread of farming families.

The loaf is dense, with a cracked crust and an earthy aroma, and it is rarely made with corn alone. Because corn has no gluten, bakers typically mix it with rye or wheat to give the bread structure and elasticity. One distinctive step sets broa apart and that is that the cornmeal is scalded with boiling water before being combined with the other flours, a technique that softens the coarse grain and lends the crumb its moist, almost chewy texture. It is a bread made for dipping into caldo verde, crumbling into migas de broa (see below), or forming a golden crust over bacalhau com broa.

In Minho, loaves tend to be smaller and darker, with a higher proportion of rye, while in the Beiras the bread can be lighter, sometimes with more wheat. The Azores also have their own version, called pão de milho. Although it shares a name, it is not the same bread, as on the islands, the crumb is softer and the dough lighter, relying more on wheat flour than corn itself.

As for where the best broa de milho comes from, opinions are deeply regional. Minho is often singled out as the heartland of broa, with villages where baking techniques have been passed down for generations. In the Beiras, particularly around Coimbra and Viseu, broa is just as beloved, often accompanying hearty stews and roast meats. Even in Trás-os-Montes, where rye is more common, broa de milho remains a part of local identity. Here in the city, broa is usually sold at regular supermarkets but, to try a nice crusty one, head straight to one of Lisbon’s best sourdough bakeries, such as Gleba (many locations across the city) or, if you’re serious about trying what is perhaps the very best broa in Lisbon, head to Manteigaria Silva (Rua D. Antão de Almada 1 C) and ask for the wood-baked one they often source from a small independent baker outside the city.

Broa de Avintes | Avintes corn and rye bread

Photo by Radio Metropolitana Porto

Photo by Radio Metropolitana Porto

If broa de milho is the everyday rustic bread of northern Portugal, broa de Avintes is its darker, more complex cousin. Named after the town of Avintes, just outside Vila Nova de Gaia, this bread has long been tied to the identity of that community.

Unlike regular broa, which combines cornmeal with rye or wheat, broa de Avintes leans heavily on corn and rye together, producing a loaf that is dense, moist, and almost malty in flavor. Traditionally, malt was also added to the dough, intensifying its sweetness and giving the crumb its darker hue. The process is slow as the dough ferments gradually, and the loaves are baked for hours (sometimes even overnight), in the fading heat of wood fired ovens. The result is a heavy, aromatic bread so filling that a single slice can stand on its own, though it pairs beautifully with cured meats, pungent cheeses, or simply a drizzle of good olive oil.

Bakers in Avintes continue to protect the tradition, and the bread is still sold locally in iconic bakeries such as Padaria Ribeiro de Avintes and Broa de Avintes D. Maria Cristina, ensuring authenticity for those who make the pilgrimage to its hometown. But for those in Lisbon, tasting a true broa de Avintes no longer requires a trip north. The bakery Massa Mãe, in the neighborhood of Benfica (Estr. de Benfica 232 A/B), mills its own grain inside the shop and produces an exceptional version of this bread, something quite rare in the capital.

Bolo da sertã | skillet corn bread from Azores

Photo by byAçores

Photo by byAçores

On the islands of the Azores, corn also found its way into daily bread, but in a form very different from the dense loaves of the mainland. The bolo da sertã is a simple skillet bread, made from cornmeal and cooked directly on a flat iron pan, the sertã, set over the fire. Its origins are humble as it came about as a practical solution for rural families who didn’t always have access to ovens, but could still produce fresh bread with basic tools and ingredients.

The texture is more compact than wheat bread but less dense than broa de milho, with a slight chew and a rustic flavor that reflects the grain’s earthiness. Each cake is formed into a flat, round shape, then baked on the hot surface until golden, developing a crisp outer layer while staying soft inside. Traditionally, it was made in small batches and eaten the same day, served with soups, stews, or a simple piece of fresh cheese.

Bolo da sertã can be found mostly in family kitchens across the islands of São Miguel, Pico, Terceira, and Faial, though it’s known throughout the archipelago. It is not a bread you will typically find in Lisbon’s bakeries as it remains connected to Azorean homes and smaller local eateries. Travelers who want to taste it at the source should head to village restaurants or family-run adegas in the Azores, where it is still served alongside typical Azorean dishes.

For those unable to travel, though, bolo da sertã is one of the easier Portuguese corn breads to recreate at home. The base is simple: about two cups of fine cornmeal, a pinch of salt, and just enough boiling water to scald the flour into a thick paste. Once cooled slightly, a handful of wheat flour is added to give it elasticity, along with a drizzle of olive oil to keep it moist. The dough is shaped into flat, round cakes, usually the size of a small plate and about a finger thick. They are then cooked slowly on a hot skillet or cast-iron pan, turning once, until both sides are golden and the inside is set. Served warm, with butter or fresh cheese, they capture the rustic but delicious flavor of the Azores in the best possible way.

Savory Portuguese dishes made with corn

Milho frito | fried corn meal cubes

Photo by Ruralea

Photo by Ruralea

In Madeira, corn took root early after its arrival from the Americas in the 16th century. The island’s mild, humid climate proved ideal for maize cultivation, and it quickly became one of the most important crops for both people and livestock. Families relied on it for porridges known as papas de milho, which were cheap and filling. These porridges were the everyday meal of rural households, eaten plain or with whatever vegetables were available. Out of this humble base came milho frito, the fried version that would become one of Madeira’s most iconic foods.

The process is deceptively simple but produces a delicious result. Cornmeal is slowly cooked with water, garlic, olive oil, and often shredded cabbage until it thickens into a firm porridge. Once cooled, it is cut into cubes or rectangles and fried until crisp on the outside but soft and creamy inside. The contrast of textures is irresistible, pairing beautifully with grilled meats or fried fish. And this is why milho frito is inseparable from another Madeiran classic, espetada, which consists of beef skewered on laurel branches and grilled over open flames. The combination of juicy meat and golden cubes of milho frito tends to be very beloved by locals and also travelers who visit Madeira.

There’s also a simpler cousin, milho cozido, which consists of the same corn porridge served plain, without frying. This version, rarely seen in restaurants today, survives mostly in Madeiran homes as a comfort food.

In Madeira, it’s difficult to avoid milho frito, and why would you want to? It is offered in nearly every traditional restaurant, piled high in generous portions. On the mainland, however, it takes a little more hunting. In Lisbon, Madeiran restaurants such as Ilha da Madeira (Rua Campo de Ourique 33) serves it as a side to classic island dishes. You’ll also find it in more casual settings, such as some bars dedicated to poncha (the fiery sugarcane spirit of Madeira), including the popular spot in Alfama Madeira Pura (Rua do Terreiro do Trigo 72), which serves milho frito cubes as a salty snack perfect to accompany your drinks.

Xerém | savory cornmeal Porridge

Photo by Teleculinária

Photo by Teleculinária

Down in the Algarve, corn takes shape in xerém, a savory porridge that has become one of the region’s most emblematic dishes and that is also known as xarém. Xerém is essentially made by slowly simmering finely ground white cornmeal into a thick, hearty base, to which seafood, meats, or vegetables are later added. The most famous versions feature clams (xerém de amêijoas) or cockles (xerém com conquilhas). The shellfish are first cooked separately, and their stock is used to prepare the cornmeal, giving the porridge its briny depth. Only once the base is ready are the bivalves folded back in, along with garlic, onions, olive oil, and sometimes a splash of white wine, creating a dish that captures the flavor of the sea.

The origins of xerém reveal a story of cultural crossroads. While maize only arrived in Portugal in the 16th century, the technique of transforming cereals into a base similar to couscous predates its introduction. The Algarve, with centuries of Moorish presence and later exposure to Mediterranean culinary traditions, already had a repertoire of grain porridges. Cornmeal found its place naturally in local cooking, producing something that looked like a distant cousin of North African couscous or Italian polenta, but with its own Portuguese accent. It was quickly adopted by fishing communities, who paired it with the shellfish and pork they had at hand.

Though most associated with the Algarve, xerém also traveled beyond. Portuguese migration and colonial connections carried the dish abroad and it appears today in parts of Cape Verde and Mozambique, where it merged with local foodways, and even in Northeastern Brazil, where versions of cornmeal mush called xerém or xerém nordestino still exist today.

Within the Algarve, there are many variations. Besides the more popular xerém de amêijoas and xerém com conquilhas, you’ll also find a more generic xerém de bivalves, which mixes several types of shellfish together. Inland villages make versions with pork, such as xerém com entrecosto (with pork ribs) or xerém com enchidos (with local sausages), while some households prepare a simpler vegetarian version with cabbage or wild greens. The texture also varies, as in some kitchens it is whisked smooth and creamy, while others leave it coarse and grainy, closer to polenta.

For those eager to try xerém here in Lisbon, we recommend visiting Taberna Albricoque (Rua dos Caminhos de Ferro 98), an Algarve inspired restaurant by chef Bertílio Gomes, that occasionally features it on the menu.

Papas de sarrabulho | pork blood porridge with cornmeal

Photo by Taste Braga

Photo by Taste Braga

Few dishes illustrate the no-waste philosophy of northern Portuguese cooking better than papas de sarrabulho. Traditionally prepared during the winter pig slaughter, this porridge makes use of pork blood simmered with broth, spices, and a mix of thickening agents like bread, rice, or cornmeal, resulting in a dark velvety dish.

In its most common form today, especially in Minho, sarrabulho relies mainly on rice for body, and is therefore known as arroz de sarrabulho. But older recipes, particularly in small villages, used cornmeal. Corn gave the porridge a heavier, earthier texture and made it even more filling, which was essential in communities where food had to sustain long days of agricultural labor. This variation still exists, although papas de sarrabulho are less frequently found in restaurants than arroz de sarrabulho.

The dish’s origins are quite practical, as nothing from the slaughtered pig went to waste, and blood, rich in nutrients, became a natural base for warming porridges. Spices like cinnamon and clove were added to temper the strong flavor, and cornmeal provided sustenance when rice was scarce or expensive.

Today, when served in restaurants, papas de sarrabulho most often accompany roast meats, particularly rojões, which are cubes of marinated and fried pork. While some may shy away from the idea of food featuring blood, in northern Portugal it continues to be celebrated as a traditional food with a strong history. This is one of those dishes worth traveling to northern Portugal for during the winter but, if you can’t truly make it, you may get lucky in Lisbon at tascas such as O Luís (Rua José Duro 29).

Migas de broa com couve | cornbread mash with greens

Photo by O Meu Tempero by Carla Sousa

Photo by O Meu Tempero by Carla Sousa

Migas de broa com couve are a way of giving new life to stale broa de milho. The bread is crumbled, mixed with sautéed cabbage or collard greens, garlic, and olive oil, and sometimes enriched with pork fat or drippings from a roast (even though fully vegetarian versions are perfectly possible and still full of flavor). The result is a dish that’s thrifty but very satisfying, with a crumbly texture reminiscent of a stuffing used for meats such as turkey in other parts of the world.

The origins of migas go back to a broader Iberian tradition of reusing bread. Across Portugal, there are countless variations of migas, often tied to wheat in the Alentejo and to corn bread in the Beiras and northern regions. What makes the corn version distinctive is its dense, earthy base, which soaks up flavors particularly well. Historically, it was the answer to the problem of what to do with broa once it hardened, as wasting food was not an option in rural households, and these crumbs became the foundation for a new dish rather than being discarded.

In some places, migas de broa evolved into festive accompaniments, especially for pork dishes. The roasted meats from the winter pig slaughter were often served with a side of these corn bread mash, turning what began as a way of stretching resources into something celebratory.

Bacalhau com broa also makes very good use of corn bread crumbs. Instead of being mixed into the pan, the broa is crumbled, seasoned with garlic, herbs, and plenty of olive oil, then spread over salt cod and baked until the top forms a golden, crunchy crust that contrasts beautifully with the tender fish underneath.

Portuguese desserts with corn

Papas de carolo | sweet cracked corn porridge

Photo by Ingredientes

Photo by Ingredientes

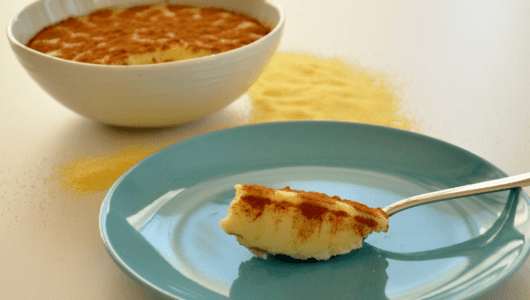

In the Beiras, one of the most traditional ways to enjoy corn is as a sweet porridge known as papas de carolo. The word carolo refers to cracked corn kernels, coarser than regular cornmeal, which give the dish a slightly grainy texture. Cooked slowly with milk, sugar, lemon zest and cinnamon stick, it becomes a simple yet comforting dessert, often served warm and customarily served with a dusting of powdered cinnamon.

Back in the day, in households that raised and milled their own corn, nothing went to waste, and carolo was the byproduct of grinding maize. Turning it into sweet papas was a way of transforming an unglamorous ingredient into something indulgent, especially for children. The dish became so ingrained in the food culture of the Beiras that a Confraria dos Carolos e Papas de Milho was founded to safeguard the tradition and promote its continuity. Confrarias are gastronomic brotherhoods, common in Portugal, that gather enthusiasts and professionals around a specific product or dish to ensure its preservation and visibility. The existence of one dedicated entirely to carolos and papas de milho says a lot about how important this humble recipe is for local identity.

Papas de carolo also connect to a wider family of Portuguese corn porridges. Across the country, variations exist under the name papas doces de milho, often made smoother with finely ground cornmeal and enriched with butter or egg yolks. In Madeira and the Azores, similar porridges appear at holiday tables, flavored with spices and sometimes raisins.

Although less commonly found on restaurant menus today, papas de carolo endure in some home kitchens of the interior of Portugal. For those curious to try them, the method consists in simmering cracked corn in milk with a pinch of salt and a strip of lemon peel for aroma, stirring often until the grains soften and the mixture thickens. Towards the end, add sugar to taste, add sugar to taste, much like you would with oatmeal. Serve warm, sprinkled with ground cinnamon.

Bolo de tacho de Monchique | cornmeal cake from the Algarve

Photo by Algarve Marafado

Photo by Algarve Marafado

In the Algarve, and particularly in the mountain town of Monchique, cornmeal takes on a sweeter expression in bolo de tacho, a dense, spiced cake with a story that stretches back centuries. Its name means “pot cake”, because it was traditionally mixed and baked in the very same pot. The shape varies depending on the size of the pan, but the result is always the same, being a quite compact, dark loaf.

Unlike the airy sponge cakes found elsewhere in Portugal, bolo de tacho is deliberately heavy and rich. Cornmeal provides the base, but the batter is layered with sugar, honey, coffee, lard or olive oil, and spices such as cinnamon, fennel seed, and sometimes even anise. Chocolate is a later addition, making the cake darker and more intense, while lemon zest lightens it slightly. The mixture is scalded with strong coffee before resting overnight, giving the flavors time to meld. Once baked in the greased pot, it emerges with a moist, almost pudding-like crumb and a glossy crust.

Historically, this cake belonged to agricultural households, where corn was the daily grain and festive baking had to rely on what the pantry provided. The recipe was later refined by the Franciscan friars at the Convent of Nossa Senhora do Desterro in Monchique in the 17th century, who are credited with popularizing it beyond the household kitchen. Over time, it became linked with rural celebrations, particularly May Day. In fact, the cake is also known as bolo de maio, because it was traditionally eaten on the 1st of May. On that morning, locals would “attack May” (atacar o Maio) by eating a slice of cake with a glass of medronho (a traditional fruit brandy), a ritual thought to fortify the body for the new season. Families would bake their own cakes and then trade them with neighbors, a friendly competition to see whose version was best.

In 2025, bolo de tacho from Monchique was officially recognized as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Portugal. We’re sorry but, for this one, you’re truly going to have to travel south to the Algarve!

If you’re curious to taste some of these traditions for yourself, join one of our Lisbon food and cultural walking tours and browse our blog for more stories that aim to bring Portuguese food culture a little closer to you.

Feed your curiosity on Portuguese food culture:

The definitive guide to bread in Portugal

The world of Portuguese sourdough: the best artisanal bakeries in Portugal

Portuguese foods inherited from the Moorish occupation

How the global journey of feijoada began in Portugal

Portuguese food projects you should know and follow

Real people, real food. Come with us to where the locals go.

Signup for our natively curated food & cultural experiences.

Follow us for more at Instagram, Twitter e Youtube