How to eat vegan the traditional Portuguese way

If you are to quickly think about traditional Portuguese food, it’s very likely that a list of animal protein-based dishes comes to mind: bacalhau in all its thousands of variations, pork simmered with clams Alentejo style, grilled octopus tentacles with baked potatoes drenched in olive oil, smoky peri-peri chicken, and so much more. Now-a-days, the image associated with the Portuguese table is one of abundance. But, for a big part of its history, Portugal’s relationship with food was actually more shaped by scarcity.

Until relatively recently – think just two generations or so ago – meat and fish were luxuries. Rural families, which made up the vast majority of the population until the middle of the 20th century, lived on what their land would provide and what could be stored through the seasons. That translated mostly into grains, legumes, greens, and olive oil. If a pig was slaughtered, it was once or twice a year, and every scrap was preserved to stretch for months, mostly in the shape of cured and smoked products known locally as enchidos. The day-to-day diet, however, was humble and remarkably plant-based.

Feat. photo by 1001 Ideias

Photo by As Receitas do Gato

Photo by As Receitas do Gato

Of course, our ancestors didn’t call it veganism, it was simply survival. Bread, beans, cabbage, and olive oil formed the holy quartet of the Portuguese table. Across the country, each region used what it had more in abundance, namely corn and cabbage in the north, bread and olive oil in the Alentejo, beans and chickpeas everywhere. Fish entered the diet when geography allowed it, along the coast or in the estuaries, but inland, people learned to extract nutrition and depth and flavor out of plants. That’s why Portuguese cooks became masters of turning “poor food” into something nourishing and soulful. You see it in açorda alentejana, the broth infused with garlic and coriander, which is essentially water, bread, and herbs elevated by technique. You also see it in migas (see photo above), another Alentejo invention born from leftover bread and whatever greens were on hand. You taste it in arroz de tomate or other versions of saucy rice known in Portuguese as arroz malandrinho, which are one of the country’s icons when we think of Portuguese comfort food.

If geography played a role in shaping the eating habits across Portugal, so did religion. For centuries, the Catholic calendar dictated fasting days when meat was forbidden, pushing cooks to find satisfying flavors in vegetables, grains, and legumes. These restrictions, combined with necessity, gave rise to a rich repertoire of plant-based dishes that survived even as prosperity returned. Ironically, as Portugal modernized and meat became more accessible, many of these recipes were demoted to the status of side dishes or, unfortunately, became Portuguese forgotten recipes altogether.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and we now see how things are changing. Many visitors to Portugal may assume that eating vegan here means hunting down a trendy café with avocado toast and smoothie bowls. Of course we have plenty of that, and even incredible restaurants that veganize typical Portuguese dishes, but there’s also some vegan magic happening in unassuming tascas and simpler eateries that, in some cases, have barely changed their menus in decades. The trick is knowing where to look and what to ask for.

In this guide, we’ll show you how to navigate local menus, spot naturally vegan dishes, and combine them into balanced, satisfying meals that taste authentically Portuguese.

Understanding how Portuguese menus work

Once you learn how Portuguese menus are organized, you’ll realize that eating vegan here is not only possible, in some cases, it can even be surprisingly easy if you know how to go about it. A typical menu in a traditional restaurant follows a familiar order, including soups, petiscos (small bites that could also be listed as entradas), mains, side dishes, and desserts. The problem is that most visitors only glance at the main dishes (pratos principais), usually full of meaty and fishy classics. If you stop there, you’ll think vegan options don’t exist. But the truth is, the real gold lies in the “humbler” sections of the menu, that is, the soups, the sides, and the petiscos.

Photo by Teleculinária

Photo by Teleculinária

Almost every restaurant, from the most rustic to the modern, serves at least one daily soup (sopa do dia). More often than not, it’s sopa de legumes, a vegetable soup made with whatever is in season, most commonly featuring a pureed base of potato, carrots, onions, garlic and perhaps another vegetable such as pumpkin, leek, turnip and/or zucchini. Leafy greens are often added afterwards, being the most common turnip greens (nabiças), spinach (espinafres), or any given type of cabbage (couve). If you’re keen on getting some more nutrition on your soup, which can be particularly handy if the options after this starter lack on plant-based protein, try to look for soups with legumes, such as chickpea and spinach soup (sopa de grão com espinafres), but it’s important to familiarize yourself with the most typical vegetarian soups in Portugal, as many of those that include legumes will also include cuts of meats by default (for example sopa da pedra, with kidney bean and cured meats). Interestingly, the ultra popular caldo verde, perhaps Portugal’s most well known soup, is usually plant-based as long as you ask for it to be served without the slice of chorizo which is customarily only added while plating. Otherwise, the soup is usually just potatoes, onions, garlic, olive oil, and a healthy dose of collard greens.

Photo by Notícias ao Minuto

Photo by Notícias ao Minuto

Then come the petiscos, that is, Portugal’s answer to the Spanish tapas. These small plates are often listed as appetizers, but native locals know they can form an entire meal if you order two or three. In a vegan context, they’re your best friend. Think of seasoned olives (azeitonas temperadas), tremoços, those briny lupini beans that locals snack on with a cold beer, or good crusty bread dipped in olive oil. Of course these are more snacks than actual elements of a meal but, when combined, they can add flavor and nutrition to your overall spread. Also keep in mind that, sometimes, a dish listed under petiscos can be made vegan with a small adjustment. If you see scrambled eggs with asparagus (ovos com espargos), for instance, you can ask simply for só os espargos, and the cook will know exactly what you mean. The same goes for cogumelos salteados, occasionally finished with butter, but just as delicious when cooked with olive oil. A polite “pode ser só com azeite, por favor?” usually does the trick.

Photo by Ruralea

Photo by Ruralea

After that, you’ll see the main dishes (pratos principais), which are, for sure, the trickiest for vegans. Most are centered around fish or meat, but don’t dismiss this section entirely, especially because, alongside meat or fish centered recipes, you may see some interesting side dishes that may not even be listed under the official side dish section, but that may be life savers for those following a plant-based diet. Look out for red beans rice (arroz de feijão) or savory bread pudding mixed with olive oil and greens (migas), which are either naturally vegan or can easily be made so.

Then there are the more official acompanhamentos, or side dishes, that will often show you that, to eat traditional vegan food in Portugal, you will most likely need to get creative with the combinations. Portuguese restaurants almost always serve mains with sides, and they’re usually available separately too. Typical options include rice (such as steamed white rice, arroz branco, or saucy tomato rice, arroz de tomate), fries (batatas fritas), boiled potatoes (batatas cozidas), greens (such as turnip tops, grelos, or Portuguese cabbage, couve portuguesa), or boiled vegetables like broccoli, carrots and green beans. Combine a couple of these and you can have a complete, satisfying meal. One that, when we think of it, would be the style of food many Portuguese would enjoy at home, until not that long ago.

Photo by NCultura

Photo by NCultura

Finally, the sobremesas, or desserts. We’ll get to vegan-friendly sweets later, but for now, know that the dessert list in a tasca often hides a few simple gems, including seasonal fruit (fruta da época, usually served peeled and sliced), baked apple with cinnamon (maçã assada), or pear poached in wine with spices (pêra bêbeda). If you see “caseira” next to any dessert, it means homemade, which is always worth asking about, as at least the staff will know what exactly went into it. Sometimes, even a few humble slices of orange with cinnamon (laranja com canela) can taste authentically Portuguese even if, let’s get real, it doesn’t hit the same spot as a sugary dessert would.

Note that, in the vast majority of cases, family-run restaurants will not put the label “vegetarian” or “vegan” next to the dishes we mention here. It’s simply rustic food and, to better understand how to go about it, especially outside bigger cities, it certainly helps to know some key words that will help you communicate with the staff more efficiently (see the glossary below).

Portuguese savory dishes that are naturally vegan

If there’s one thing Portuguese cuisine teaches us, it’s that simplicity and flavor are not opposites.

Soups

Soups are an undisputed Portuguese staple. In fact, long before they became the prelude to a meal, they were the meal! Particularly when enjoyed with a few slices of Portuguese bread, which varies accordingly to region. As mentioned above, the most common is sopa de legumes, a thick vegetable soup you’ll find everywhere from Lisbon to the Azores. Each cook makes it differently, but it’s almost always a mix of pumpkin, carrot, potato, courgette, cabbage, and onion, bound together by a generous drizzle of olive oil. Pouring more olive oil when the soup is already platted can be a bonus, to make the most of its nutrients, namely the antioxidants and polyphenols. As olive oil is always present on the Portuguese table, you can do this to taste.

Photo by Paul Goyette on Wikipedia

Photo by Paul Goyette on Wikipedia

In northern Portugal, caldo verde is the ultimate soup. This green soup, made from thinly sliced collard greens (couve galega) and potatoes, is traditionally enriched with a few slices of chouriço, but in truth, it needs no meat to taste whole. Travel south, and you’ll find açorda alentejana, one of Portugal’s best examples of resourceful cooking. It’s just water, garlic, coriander, olive oil, and stale bread, transformed into a fragrant comforting broth. The egg you sometimes see floating on top came later, as the ancient version was vegan by default, and you can simply ask for it this way (sem ovo). The Alentejo is also home to gaspacho alentejano, a chilled tomato and cucumber soup (pictured above) eaten in summer, not to be mistaken for the blended Spanish gazpacho, as the Portuguese one is clear, chunky, and closer to a salad with liquid than an actual soup. When the weather cools, sopa de tomate takes its place as one of the region’s most comforting staples. Made with ripe tomatoes stewed slowly with onion and garlic, it’s often finished with a poached egg on top, but since the egg is simply a finishing touch, you can easily ask for it sem ovo and enjoy a flavorful vegan version of this rustic classic. A similar preparation exists in Madeira, known as sopa de tomate e cebola, where the base of tomatoes and caramelized onions creates a broth that is slightly sweeter. In Madeira it is also common to find it topped with an egg, so the same rule applies, and you can just ask for it sem ovo to enjoy it fully plant-based.

Further north, during autumn, you might encounter sopa de castanha, made with chestnuts from Trás-os-Montes. It’s hearty and earthy, but do check that the version you’re ordering doesn’t include cream (natas), as some modern adaptations do. In fact, even when a soup’s name sounds vegan, like for example buckwheat soup (sopa de trigo) in Madeira or fennel soup (sopa de funcho) in the Azores, it’s wise to ask, because these traditional broths often include bits of cured meats or bacon for flavor. As a general rule, the safest and most widely available vegan soups across the country are sopa de legumes, sopa de tomate, and gaspacho alentejano, all typically made with olive oil, vegetables, and water, with no use of meat stock.

Savory dishes based on bread

If you find yourself eating in the Alentejo or Ribatejo, bread isn’t just served on the side, and it’s actually often the foundation of the meal. The region’s most famous dishes are proof that necessity can turn into something delicious. Migas alentejanas, for example, transform leftover bread into something glorious. The bread is torn up, fried gently with garlic and olive oil, and mixed with greens or asparagus until it forms a fragrant, golden mass. When done the traditional way, without meat juices or sausages, it’s entirely vegan. Then there’s açorda de alho or açorda de tomate, variations of the same concept, featuring garlic mashed with salt, olive oil, and herbs, into which hot water and bread are mixed until it becomes a thick, spoonable porridge. Some restaurants complete it with poached eggs or cod, but the original rural versions are simple and plant-based by default, so just make sure to ask for your serving without those finishing touches.

Photo by W360

Photo by W360

If you venture further south to the Algarve, you might come across xerém, a coarse cornmeal dish cooked like creamy polenta, enriched with garlic and olive oil. The seafood version is the most common, but plain xerém, especially in traditional inland taverns, is naturally vegan. In Madeira, the same spirit appears in milho frito (photographed above), which are small golden cubes of fried cornmeal, crisp on the outside and creamy within. They’re served as a side but taste so good they often steal the show, and would also make for a great snack any time of the day, especially while sipping a cold drink.

Typical Portuguese vegetables and greens

When you ask for vegetables in Portugal and they come as a side to a main dish (usually featuring meat or fish), you will most likely be served boiled vegetables (legumes cozidos) that are often a little mushy. We’re talking mostly about potatoes, carrots, broccoli and green beans. But eating leafy greens the Portuguese way can be more delicious, as these are often sauteed in generous amounts of olive oil and garlic, resulting in something nutritious and very flavorful too. Sautéed turnip tops (grelos salteados), which are slightly bitter but very aromatic, can be found almost everywhere in central and northern Portugal.

Photo by Petitchef

Photo by Petitchef

There’s also tomatada, a slow-cooked tomato stew from the south, which balances sweet and tangy with olive oil and garlic. Tomatada often comes with poached eggs but, same as with açorda above, you can simply ask for it without. It goes well with rice to soak up the juices but it’s often also served with fries.

Photo by Ruralea

Photo by Ruralea

Cenouras à algarvia, that is boiled carrots marinated in paprika, vinegar, and garlic, are a cold appetizer typical from the Algarve but that, thankfully, can often be found in the petiscos menu of restaurants from other parts of the country too, particularly around Lisbon.

Photo by Intermarché

Photo by Intermarché

And no summer table is complete without pimentos assados, roasted bell peppers drizzled with olive oil and vinegar, the star side dish usually served with grilled sardines during the warmer months but that are delightful on their own or to make a salada mista (the simplest and most common salad you’ll find across Portugal, featuring lettuce, tomato and onions), a little more interesting.

Rice and legumes, Portuguese style

Portuguese kitchens are full of typical dishes based on beans and legumes, that have sustained generations. Arroz de tomate, slightly soupy tomato rice, is one of the simplest pleasures you can order, and it’s quite ubiquitous. Arroz de feijão, rice with red beans cooked in tomato and olive oil, appears across the country and is fully vegan unless the cook adds sausage (this is not that common but, when in doubt, simply ask). Ordering a soup, kidney bean rice and a nice salad, makes for a complete and tasty meal, that is very Portuguese indeed!

In northern and central Portugal, one of the most satisfying plant-based dishes you can encounter is migas de broa com couve e feijão. It’s a hearty combination of broa (cornbread), cabbage, and, most commonly black eyes peas (feijão-frade), though in the central Beiras region you might also find it prepared with feijoca, a plump cousin of white bean that gives the dish a creamy texture. Cooked slowly in olive oil and garlic, these migas are dense, rustic, and filling enough to stand alone as a full meal, with protein from the beans, fiber from the greens, and starches from the broa.

Photo by Receitas ao Desafio

Photo by Receitas ao Desafio

Meanwhile, in the Azores, broad bean stew (favas guisadas) offers a different take on broad beans. Unlike the mainland version favas com enchidos, which traditionally includes sausages, the island style, particularly in Pico and Terceira, is lighter and typically vegan by default. The beans are stewed with lots of onions (cebolada), sometimes a little tomato, olive oil, and herbs, creating an aromatic dish that relies entirely on the flavor of the vegetable ingredients rather than meat. At most, some cooks might use a meat-based stock, so it’s worth asking, but otherwise, favas com cebolada remains one of the simplest and most authentically plant-based dishes in Azorean cooking.

Vegan-friendly Portuguese desserts

If there’s one thing Portuguese cuisine is not known for, it’s restraint when it comes to eggs. Walk into any pastelaria, and you’ll be greeted by a glass counter glowing with yellowish options, including pastéis de nata, convent sweets, and other typical Portuguese pastries. Delicious, yes. Vegan, not even close. That said, times are changing. At least in Lisbon and Porto, a handful of bakeries now specialize in vegan versions of traditional sweets, even the iconic Portuguese custard tart. In Lisbon, places like Vegannata or Nat’elier have mastered the art of recreating the pastel de nata without eggs or dairy, while in Porto, Padoca Vegan offers its own take on the classic, proving that Portuguese pastry can evolve without losing its soul.

Photo by Panizende

Photo by Panizende

Still, if you wander into an ordinary pastelaria rather than a vegan shop, it’s worth knowing that a few items behind the counter might already be vegan by default, even if they’re not labeled as such, and even if the staff can’t confirm it with certainty. The secret lies in understanding how traditional Portuguese pastry production works. Most pastelarias use vegetable margarine (margarina) instead of butter, largely because it’s cheaper and easier to handle when it gets warm. So, when you see pastries that clearly don’t contain eggs or milk, for instance, plain puff pastry croissants (croissant folhado – looking like the one in the photo above), sweet rolls with candied fruit (caracóis), or simple palmiers without toppings or fillings, there’s a good chance they’re vegan. Avoid croissant brioche, as those do contain eggs and milk, but laminated pastries made only of flour, margarine, sugar, and salt are often plant-based. The only detail to watch for is the occasional egg wash brushed on top to make pastries shiny. If a croissant folhado looks matte and flaky rather than glossy, it’s probably safe. These aren’t guarantees, of course, and most cafés won’t know for sure, but it’s an insider tip worth remembering. In a country where butter is rarely used in traditional pastry store kitchens, you might just find that your morning coffee comes with a vegan croissant folhado by happy accident.

But while the pastelarias, that uniquely Portuguese hybrid between café and pastry shop, are the domain of baked goods like pastéis de nata and croissants, the desserts you’ll find in restaurants belong to a different world. Here, sweets are meant to be eaten with cutlery, not picked up with your hands. You’ll rarely find a pastel de nata on a restaurant dessert list, just as you won’t see mousse de chocolate or maçã assada in a pastelaria. So, after exploring the pastry counter, it’s worth looking into what restaurants may have in store when it comes to vegan-friendly options of Portuguese sweets.

Let’s start with the simplest and most widespread, which is obviously fruit. We understand that this may not sound super exciting to some but, in Portugal, fruit is a legitimate dessert option for many, not necessarily vegans. Ordering fruit in a restaurant has its perks, as it means that someone else does the work for you. If you ask for an orange (laranja, which can also be served with a touch of cinnamon, in that case called laranja com canela), it will come already peeled and neatly sliced. In summer, honeydew melon (melão) and cantaloupe (meloa) are common choices, served in thick wedges or cubed, and perfectly chilled. Pineapple (abacaxi or, if you’re in the Azores, ananás dos Açores, which is considerably pricier) is another restaurant classic, usually sliced and elegantly presented with a fork and knife. For a mix of a little bit of everything, simply order a fruit salad (salada de frutas), which wouldn’t be unheard of with a little splash of Port wine, which you can request to taste.

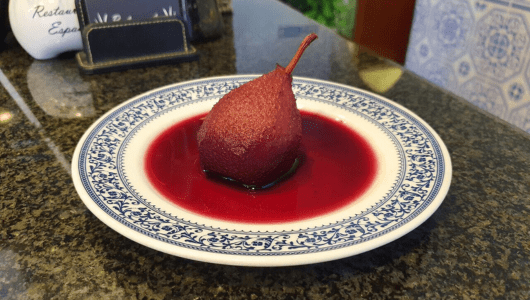

Photo by Restaurante Espanhol on TripAdvisor

Photo by Restaurante Espanhol on TripAdvisor

Then there are the baked and stewed fruit desserts, baked apple (maçã assada) being the most common of them all. This classic consists of an apple cored, sprinkled with sugar and cinnamon (sometimes a splash of port), and baked until tender. It’s fragrant, and comforting, and essentially Portugal’s answer to apple crumble, without the crumble. Pêra bêbeda (literally “drunken pear”) is another that turns up in home kitchens and many restaurants, consisting of pears poached in red wine with sugar, cinnamon, and clove, served chilled.

Photo by Tradições Doces

Photo by Tradições Doces

Fruit preserves and compotes are another option of the vegan-friendly sweet world. Marmelada, the quince paste that gave English “marmalade” its name, is made only with quince, sugar, and lemon, and it’s been part of Portuguese tables for centuries. It’s usually served with slices of cheese, but you can ask for it with bread instead, which is how it was traditionally eaten in more modest homes. Doce de abóbora, pumpkin jam cooked slowly with sugar, cinnamon, and sometimes a bit of orange peel, is another staple. You’ll usually find it served with cottage cheese but you can also spread it on toast or even eat a little with a spoon, for a little purely plant-based sweet ending.

How to combine dishes for a complete vegan meal

A satisfying, balanced vegan meal in a tasca usually comes together when you anchor it on one legume dish (protein), then add one vegetable dish (fiber + micronutrients), one starch (energy), and let olive oil be your fat. Soup can open or round off the meal. If you remember nothing else, remember this: legumes + grains/starch + greens + olive oil is the Portuguese plant-based sweet spot.

Start with soup because it’s a safe choice almost everywhere and it’s usually quite tasty. Sopa de legumes or caldo verde sem chouriço gives you vegetables, warmth, and satiety without stealing the show. From there, choose a protein anchor that you will find in traditional restaurants, such as rice with red beans (arroz de feijão), migas mixing corn bread, beans and lots of shredded greens or, if you’re in the Azores, something like stewed broad beans with onions. These options give you honest plant protein the way locals also eat it at home.

Photo by Solinca

Next, add greens or a cooked vegetable. Something like sautéed turnip tops (grelos salteados), cabbage (couve), assorted boiled veggies (legumes cozidos) or, during summer, roasted bell pepper salad (salada de pimentos assados). If iron absorption is on your mind, pairing legumes and greens with a good source of vitamin C such as tomato, peppers, or a squeeze of lemon helps, even a humble laranja com canela after the meal does a job.

Photo by Knorr

Photo by Knorr

Now choose your starch, particularly if your protein option above doesn’t contain it yet. At least this is one section where you’re actually spoiled for choice as most are naturally vegan. Choose from plain white rice (arroz branco) or boiled potatoes (batata cozida), to more flavorful options like slightly brothy tomato rice (arroz de tomate), to roasted potatoes cracked and drenched in olive oil (batatas a murro).

You can put all of this together in ways that feel like real Portuguese eating. A classic everyday set could be soup + saucy rice with red beans + sautéed greens, with olives on the table for extra fat and satisfaction. Another very normal combo could be sopa de legumes + migas with beans and cabbage + fruit.

You can also build a full meal from petiscos, but keep the need for protein in mind. Azeitonas temperadas and pimentos assados are great, yet they’re fat and veg. Add protein with tremoços, that is, lupini beans, a very Portuguese and very protein-dense snack, and/or a plain bean or chickpea salad ordered without tuna (sem atum) and with no egg (sem ovo). Finish with bread or potatoes for the carb and you’ve got balance without ever touching a “main”.

A few small pitfalls to dodge so a good plan stays vegan and balanced would include asking if soups are made with meat stock (“É caldo de legumes?”), and request caldo verde without meat (sem chouriço).

Navigating traditional restaurants like a local (with mini glossary)

Once you understand how Portuguese restaurants work, you’ll realize that eating plant-based here is often made possible with good communication. Start by remembering that most traditional Portuguese eateries are family-run. The waiter might also be the owner, and the cook is probably a relative who has been making the same dishes for decades. They may not be used to hearing the word “vegan”, but they do understand when you clearly say without meat, fish or eggs (sem carne, sem peixe, sem ovos). If you’re polite and appreciative, most people will go out of their way to adapt a dish for you. The key is to be direct but kind and, instead of explaining what vegan means, just describe what you don’t eat.

Photo by Barzin

Photo by Barzin

If the server brings small bites to the table before you’ve ordered, usually olives (azeitonas), bread (pão), butter (manteiga), cheese (queijo), or some sort of pâté, this is called couvert. It’s not a free appetizer, but neither is it a trick, as it’s simply part of Portuguese dining culture. The important thing to know is that couvert can be charged in two different ways. In some restaurants, you’re billed per item, which means you’ll only pay for what you actually eat. If you take the olives but ignore the butter and cheese, only the olives appear on your bill. In other places, couvert is charged per person as a set price (particularly when presented all together in a platter, as pictured above), covering the whole assortment that lands on the table, whether you eat all of it or not. You can always check the price in advance, as by law couvert must be listed on the printed menu, and it’s usually among the first items. If you don’t care for the animal-based products like butter, cheese, cold cuts, or pâtés, you can ask the staff to replace them with more plant-based options or simply skip them. Something as simple as “Só as azeitonas e o pão, por favor” works perfectly. Most restaurants will happily bring you a little extra olive oil for dipping if you ask, which can even be better than the butter you’d be turning down anyway. Since you’re paying for the couvert in one form or another, you might as well make the most of what you enjoy and, in Portugal, good bread, good olives, and good olive oil are always worth lingering over.

Menus in small restaurants are short, and daily specials (pratos do dia) change according to what’s available. That flexibility can work in your favor and, if you ask, many cooks can prepare a vegetable plate (prato de legumes) or a mix of side dishes (acompanhamentos) on the spot. Saying something like “Pode fazer um prato só com acompanhamentos?” will help.

Here’s a mini glossary of useful phrases that will help you navigate menus and conversations [almost] like a local. You don’t need to sound fluent, just polite and friendly. Portuguese people appreciate the effort, and you’ll find that even just a few words can go a long way.

- Sou vegan / vegetariano(a). | I’m vegan / vegetarian.

- Não como carne nem peixe. | I don’t eat meat or fish.

- Sem carne, sem peixe, sem ovos, por favor. | Without meat, fish, or eggs, please.

- Não como produtos de origem animal. | I don’t eat animal products.

- É feito só com legumes? | Is it made only with vegetables?

- Tem leite, ovos ou manteiga? | Does it contain milk, eggs, or butter?

- Pode fazer sem isso? | Can you make it without that?

- Pode ser só com azeite, por favor. | Can it be made only with olive oil, please?

- Tem sopa de legumes hoje? | Do you have vegetable soup today?

- Queria a sopa sem chouriço, se faz favor. | I’d like the soup without sausage, please.

- Pode fazer um prato só com acompanhamentos? | Could you make a plate just with side dishes?

- Só as azeitonas e o pão, por favor. | Just the olives and the bread, please. (when the couvert arrives, and you don’t want the cheese or other animal based items that will normally be served)

- Pode fazer sem o atum e o ovo, por favor? | Can you make it without the tuna and egg, please? (useful for bean salads, mostly)

- Está delicioso! | It’s delicious! (always good to end with this one)

Learn just a handful of these, and you’ll be able to order anywhere in Portugal with ease. With some grace, you will not come across as a picky eater, but as someone genuinely engaging with the culture. A friendly “obrigado” (said by men) or “obrigada” (by women) at the end will do more for your experience than any translation app ever could.

Once you learn how to navigate traditional eateries, Portugal can actually be a surprisingly rewarding place to eat vegan. For more tips like these, subscribe to the Taste of Lisboa newsletter and follow our regular publications on Instagram.

Feed your curiosity on Portuguese food culture:

The best Portuguese vegan food and wine in Lisbon

Portuguese chefs redefining vegetarian and vegan cuisines

Portuguese food projects you should know and follow

The ultimate guide to olive oil in Portugal

Real people, real food. Come with us to where the locals go.

Signup for our natively curated food & cultural experiences.

Follow us for more at Instagram, Twitter e Youtube